Construction of fault-tolerant quantum computation with threshold theorem

Advisor: Dr. Sergii Strelchuk (DAMTP)

Introduction

Richard Feynmann once famously said, ‘Nature isn’t classical, dammit, and if you want to make a simulation of nature, you’d better make it quantum mechanical, and by golly it’s a wonderful problem, because it doesn’t look so easy’. Ever since then, quantum computation based applications have been brought into the limelight and various platforms such as quantum dots, ensembles of trapped ions, photonic systems and superconducting circuits have been studied to achieve the physical realization of a quantum computer. It is widely recognized that some quantum algorithms can be exponentially more efficient at problem solving compared to classical ones. But despite decades of research in the field, we are still far from building a complete quantum computer that could solve ‘interesting’ algorithms and satisfies DiVincenzo’s criteria. Scalability is a major obstacle from an engineering prospective while decoherence, e.g. leaking information to the environment and errors in computation put a fundamental question in the theoretical field. Without error correction, accumulated noise will disturb the system and ruin the results. Apart from that, quantum computing relies on unitary operations and it is made from extremely small components, so quantum states are more susceptible to more types of errors than classical computers. Therefore, we are in need of a fault tolerant scheme.

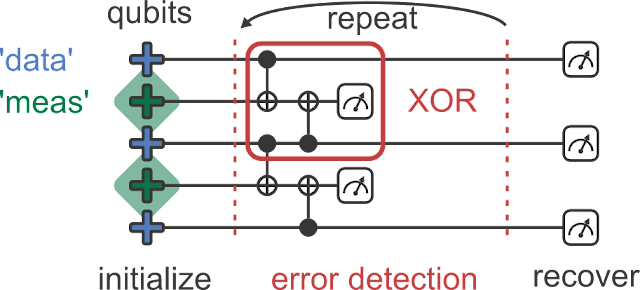

Fault tolerance involves modifying a circuit designed for a specific algorithm by adding extra qubits and gates to make it more resilient to noise. Unlike the normal error correction procedure, where Alice and Bob use a quantum channel with encoded states and a quantum error-correcting code (QECC) assuming perfect encoding and decoding schemes, fault tolerance accounts for additional noise and aims to control error propagation. Error propagation refers to the scenario when a two-qubit gate correctly interacts with two qubits, but one of them has an error. This results in a two-qubit error relative to the ideal world with no errors, such as when a bit flip (X) error occurs on the first (control) qubit, followed by a perfect CNOT gate that flips the second qubit at an unintended time. Fault tolerance addresses this issue by mitigating error propagation and preventing it from spiraling out of control.

In the next section, several error correction algorithms will be introduced. And in section 3 two error models are explained with some crucial assumptions being made. Relevant error correcting code is state in section 4 that will lead to the idea of Threshold theorem. Finally, some threshold-specific codes are described to illustrate the power of such theorem in quantum computation.

Error correction algorithms

Classical algorithm

To achieve a state-of-art fault tolerance computation, we need to start simple. So let’s first have a brief review on problems we might have when applying the classical algorithm on quantum computation.

A straightforward method for recovering information after errors have occurred involves making at least three copies and using majority voting. This is known as repetition code. However, this approach is not suitable for quantum computers due to several reasons. Firstly, it’s impossible to clone unknown quantum states. Secondly, taking a majority vote requires learning the encoded information through measurement, which destroys quantum coherence. Finally, binary information only needs to consider one type of error, bit flip, while quantum states are susceptible to a wide range of possible errors.

CSS code

Fortunately, Shor and Steane discovered a solution to these challenges. Instead of copying information to introduce redundancy, they used entangled states supported by additional bits. To avoid collapse of quantum information during error correction, they made a partial measurement that extracted only the error information (syndrome) and left the encoded state untouched. To handle the continuum of possible errors, they recognized that every error could be represented as a linear combination of standard errors, including no error, bit flip, sign flip, or both. Furthermore, they found that linear combinations of correctable errors could also be corrected, enabling the discretization of error possibilities.

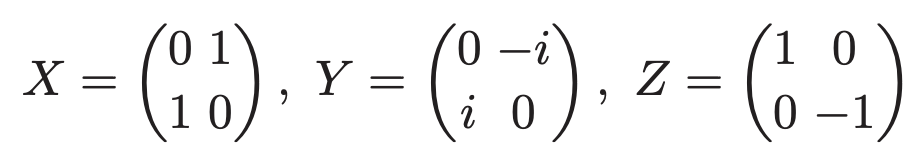

This is called CSS codes. The foundation of this quantum error correction is built upon two main observations. Firstly, any fault or quantum operation on a qubit can be expressed as a linear combination of four fundamental operations: the identity (no error), a bit flip ($\ket{0} \xrightarrow{} \ket{1}$), a phase flip $(\ket{0} \xrightarrow{} \ket{0}, \ket{1} \xrightarrow{} -\ket{1}$), or a combination of both bit and phase flips. Bennett et al. initially proved that it is sufficient to correct only these four types of errors. To correct bit flips, one can use similar methods to classical error-correcting codes. To correct phase flips, another observation comes in handy: a phase flip is equivalent to a bit flip in the Fourier transformed basis. Therefore, one can first correct bit flips in the original basis, then correct bit flips in the Fourier transformed basis, which translates to correcting phase flips in the original basis.

Transverse gate

Another way to achieve error correction is to use transverse gates. A transversal gate is essentially a tensor product of single-qubit gates, which ensures that errors cannot spread. For instance, the first qubit of the initial block interacts only with the first qubit of the subsequent block, and the same applies for the remaining qubits. Nevertheless, utilizing solely transversal gates cannot achieve a universal set of gates. The number of qubits required for a fault-tolerant circuit can exceed the number of qubits needed for a noise-free version of the same circuit. This is due to the additional qubits required for encoding data in a QECC and the ancilla qubits used in a fault-tolerant protocol. And this brought up a very important parameter: the overhead of a fault-tolerant protocol, which is the proportion of the total number of qubits used in a fault-tolerant circuit to the number of qubits in the unencoded version of the circuit. We will come back to this later.

Error model

Each error correction algorithms should be tested out on a circuit model. And these specifically defined models are called error models. Note here we will combining the definitions of circuits model and error model, which basically are different components inside one fault-tolerant circuit. Before stating each model, we need to know what error network is. It is a way to depict a quantum network that experiences noise, which involves identifying error locations, where errors may arise. By generating networks that account for all possible error combinations, we can represent the behavior of the noisy quantum network. This collection of networks is referred to as an error expansion of the network. To determine the final computation state, we sum the states linked with each part of the error expansion. Operational errors are positioned after each gate, with the exception of measurements and state preparation. Memory errors exist on every bit between operations.

Back to the error model, the primary assumption regarding noise in this study is that it is local, meaning that the noise affecting different gates and qubits is independent in both time and space. This assumption may be relaxed slightly by allowing exponentially decaying correlations in error network. Such assumptions are made in classical scenarios and are likely to be valid in physical implementations of quantum computers. Therefore, we can, in the presence of local noise, consider two different error models:

- Independent stochastic errors, which is the most straightforward model. It assumes that errors are distributed independently and randomly at each error location, and the associated probability is the probability of an error occurring at an error location.

- An adversarial error model, in which an adversary selects errors subject to any other constraints to cause the most trouble possible. For example, an adversarial locally decaying error model allows the adversary to select the locations and types of errors provided that the likelihood of a large group of qubits all having errors is exponentially decaying with the number of qubits.

Adversarial error models are frequently used to limit error models with complicated but unspecified correlations and are particularly useful in fault tolerance since complicated correlations can result from error propagation in a noisy circuit.

Quantum error correcting code

With all that said, we cannot ignore one crucial aspect, quantum error-correcting code (QECC), and one of the most popular choices is the stabilizer code. Mathematically speaking, these code consists of operations called Pauli operators. And it belongs to the larger Clifford group which has some very interesting conserving properties.

This type of QECC encodes k logical qubits into n physical qubits, forming a subspace of ($\mathit{\mathbb{C}}2)^{\bigotimes n}$ with a dimension of 2k. The stabilizer formalism, developed by Gottesman, allows codes to be described as the kernel of a linear operator, just as in classical coding theory.

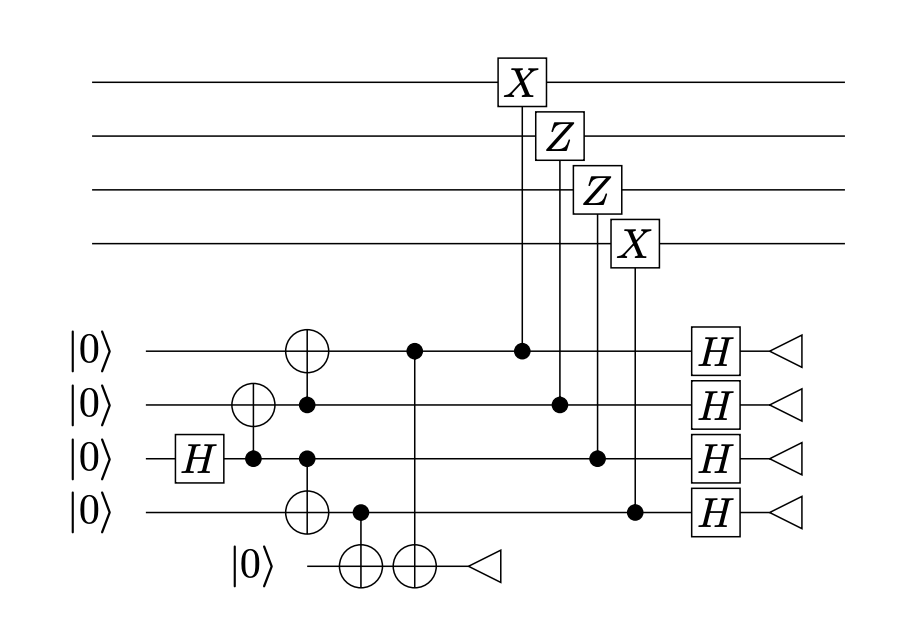

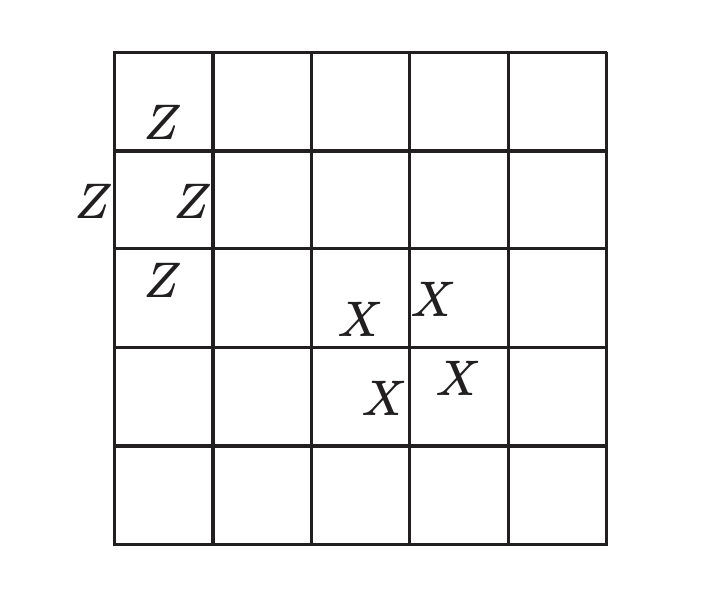

surface code

The surface code is a particularly interesting type of stabilizer code, often defined on a square lattice with qubits located on the edges. For each face of the graph, the stabilizer has a generator that is a product of X over each qubit on an edge bordering that face, and for each vertex, a generator that is a product of Z over each qubit on an edge ending at that vertex. The graph can be on a non-trivial two-dimensional manifold, such as a torus, but practicality dictates setting appropriate boundary conditions at the edges of the surface, including possibly leaving holes, to achieve the desired number of logical qubits.

However, even with good error model and QECC there is still a loophole in our assumptions: many types of errors that occur in real quantum devices cannot be represented with stochastic errors. For example, unitary over-rotation of operations and small, but non-negligible, interactions between nearby qubits can give rise to such errors. Therefore, an explicit construction is necessary to establish an error threshold. If each gate in a physical implementation of a quantum network has an error less than this threshold, it is possible to perform any quantum computation with arbitrary accuracy.

Thus entering the threshold theorem.

Threshold theorem

We will give the definition as below from Gottesman:

\emph{There exists a threshold value $p_t$ with the following property: If the error rate p per physical gate or time step is below $p_t$, then for any $\varepsilon$ $>$ 0, there exists a fault-tolerant protocol such that any logical circuit of size T is mapped to a circuit with polylog($\frac{T}{\varepsilon}$) times as many qubits, gates, and time steps, and the output of the fault-tolerant circuit is correct except with probability $\varepsilon$}

In practice, the threshold theorem can be somewhat misleading since it implies that there is a single target value, denoted as $p_t$, that should be aimed for in all efforts to construct a functional quantum computer. However, this is not entirely accurate since the exact value of the threshold is highly dependent on the assumptions made about the system, including the specific fault-tolerant protocol being used and the details of the error model.

Also, the standard threshold theorem replaces a logical circuit consisting of m qubits and T gates with a fault-tolerant circuit that uses O(m polylog(mT)) qubits. While the asymptotic scaling of overhead is favorable, the constant factors, which are hidden by the big-O notation, can be quite large. For the most efficient known protocols, these factors range from hundreds to thousands, while for protocols maximally optimized for high threshold, they can reach billions. Although the error rates in the best qubits created so far are approaching the level required for fault-tolerant protocols, the number of qubits that can be reliably realized is still relatively small in practice. Here we will give some example on such protocols.

LDPC code

The first one is Low-density parity check (LDPC) codes. Previously we have seen surface code, which is a subset of LDPC called low-rate LDPC. But now, we will introduce high rate LDPC, which are capable of correcting as many or more errors as a large surface code. Such codes can in principle remove the polylogarithmic overhead from the threshold theorem, allowing a fault-tolerant protocol with constant qubit overhead. Also, high-rate LDPC codes offer a distinct advantage over surface codes in terms of “single-shot” decoding. This implies that error correction can be performed much faster, in a constant time irrespective of the code size, while surface codes take longer to decode larger codes.

However, there is one inherent drawback to high-rate LDPC codes which is hard to circumvent. Because these codes require a high connectivity in order to rapidly spread out the information in their many logical qubits, LDPC codes with a nonvanshing rate cannot be laid out so that all stabilizer generators are geometrically localized in two dimensions, or indeed any finite dimension. This means that high-rate LDPC codes are most suitable for hardware platforms which allow long range gates with little or no extra cost. It may also be possible to lay out a fault tolerant LDPC code-based protocol in such a way that only a handful of long range gates are needed during the protocol, or even none at all, even though the stabilizer generators themselves are not all localized.

Concatenation code

We might consider another class of codes which can be arranged non-locally in 2D or even better 1D with a fault-tolerant threshold. This is the case for concatenation code.

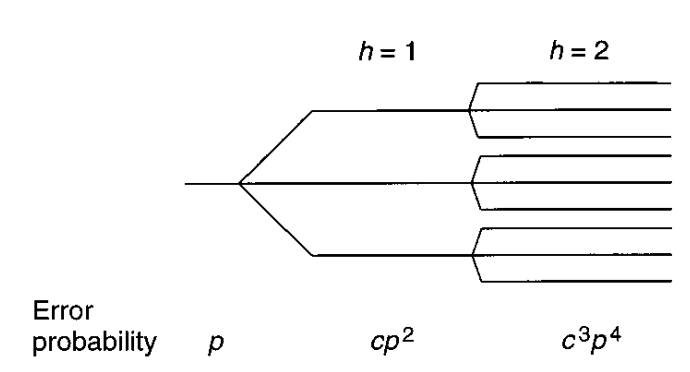

The basic idea behind concatenation is to reduce the error rate of a quantum channel by breaking it down into several smaller channels, each with a lower error rate. The individual quantum codes, also known as inner codes, are designed to correct errors that occur within each smaller channel. The resulting larger code, also known as an outer code, can then correct errors that occur across multiple smaller channels. For instance, a common method of concatenation involves using a simple error-correcting code, such as the three-qubit bit-flip code or the five-qubit code, as the inner code. This inner code is then concatenated multiple times, with additional error-correction steps applied to the resulting larger code. The outer code can be a stabilizer code, such as the nine-qubit code, or any other suitable code.

Concatenation can significantly improve the overall error-correcting capability of a quantum code, as the error rate decreases exponentially with the number of concatenated codes. However, this comes at the cost of increased computational complexity and the need for more qubits.

Expander code

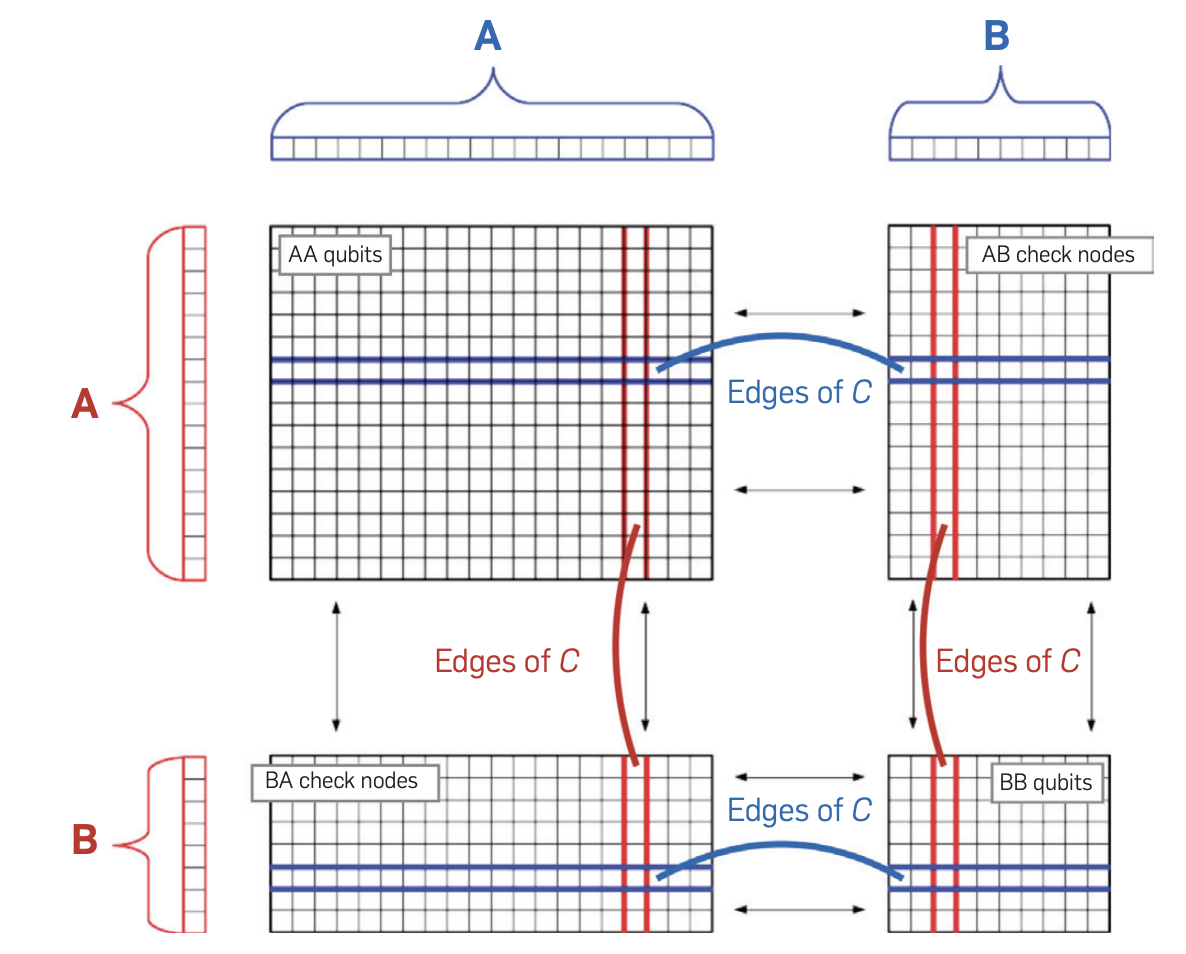

A recent proposal involves yet another new quantum error correction scheme that uses quantum expander codes to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant overhead. The scheme utilized the concept of expander graphs.

The basic idea is to create a graph with a high degree of connectivity between its vertices, such that any local perturbation affecting a small number of vertices has a minimal effect on the overall structure of the graph. This property makes expander graphs ideal for use in error-correcting codes, as errors that affect only a small number of qubits can be corrected using information from the rest of the code.

In quantum expander codes, the qubits of the code are arranged in a two-dimensional lattice, with each qubit connected to several of its nearest neighbors. The code also includes a set of stabilizer generators, which are measurements that detect errors in the qubits and are used to correct errors by applying appropriate operations.

One of the key advantages of quantum expander codes is their ability to protect against both bit-flip and phase-flip errors using a single set of stabilizer generators. This is achieved by using a special type of measurement, called a “parity check” measurement, which detects both types of errors simultaneously. To correct errors, the code uses a technique known as “flag flipping,” which involves flipping the values of certain qubits to correct the errors detected by the stabilizer generators. This is followed by a process of “syndrome decoding,” which uses the measurement outcomes from the stabilizer generators to determine which qubits need to be flipped.

But again, the downside is that, measuring the syndrome is simple in the sense that one needs to act on a small number of qubits, but the qubits will in general not be geometrically local.

Conclusion

The threshold theorem in quantum fault tolerance is a fundamental result in quantum computing that has significant implications for the development of practical quantum computers. The theorem provides a threshold value for the error rate in a quantum computing system, above which it becomes increasingly difficult to perform fault-tolerant quantum computations. One of the most important tools that has emerged from the threshold theorem is the surface code. And it has been the subject of extensive research in recent years. Another important technique that has emerged from the threshold theorem is the use of expander codes. Expander codes are a family of quantum error-correcting codes that are highly efficient in terms of their use of resources, we have seen that it uses algebraic and geometric property to make fault-tolerant quantum computation possible with few extra qubits. This is in great contrast to conventional approaches to fault tolerance. The result depends on having no geometric constraints, on fast classical computation, and above all only works in the asymptotic limit.

The development of error models is also critical for understanding the performance of quantum computing systems and for developing strategies for mitigating the effects of errors. Various error models have been developed to study the effects of errors in quantum computations, including the depolarizing model, the amplitude damping model, and the phase damping model.

One may be inclined to assume that there is a necessary tradeoff between performing lengthy logical computations and overhead. The reasoning behind this conjecture is that since the code must be able to correct more errors during a longer computation, it may require more overhead. However, it’s important to note that there is no such tradeoff for pure quantum error correction. If gate errors are not an issue, and only errors that arise during transmission through a noisy quantum channel need to be corrected, it is possible to transmit k logical qubits using n physical qubits with a constant error rate p per qubit sent through the channel. As n grows larger, k/n can approach a constant rate R, which is the channel capacity of the noisy communications channel. Additionally, even for relatively high error rates, a constant R can be achieved without compromising on data rate p. As research in quantum computing continues to progress, it is likely that the threshold theorem will continue to play a critical role in guiding the development of fault-tolerant quantum computing systems.

Download the full version here